Let that sink in.

Photo Credit: @MissMolly3286

One person, one vote. This phrase is the very core of democracy, the ultimate statement of human equality. For many us Americans, our democratic process is an integral part of our nation’s identity, and yet America is home to the most malproportioned legislature in the world. As of 2011, 50% of our U.S. Senators represented only 14% of the American people1.

This disparity arises because each state has two senators regardless of the number of people that live there – the 500,000 people that live in Wyoming have the same representation as the 38 million that live in California. To understand how this came to be, we have to go all the way back to the founding of our nation.

As the 13 colonies were considering entering into a republic, the small states feared that their needs would never be represented by the larger ones, and as such a compromise was created such that there would be two legislative bodies: the House and and the Senate.

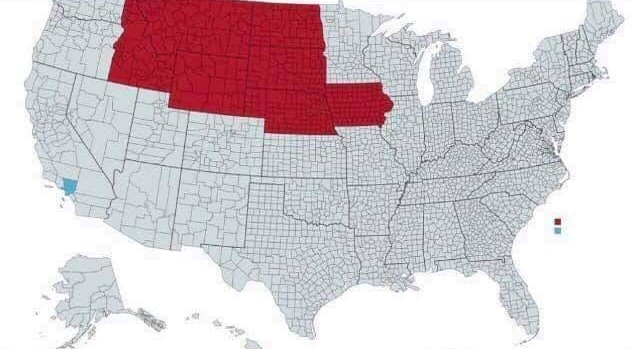

The first, and perhaps most serious impact of the way the Senate is proportioned is the way in which it disadvantages ethnic minorities. Small states (which a shall refer to the 26 states whose populations each make up less than 1.5% of the national total) are 83.4% white, and yet they receive the same representation in the Senate as the larger and more ethnically diverse states (which a shall refer to the 12 states whose populations each make up more than 2.5% of the national total) , which are only 44.2% white. This correlation means that whites receive proportionally more representation in the Senate than other ethnic groups do2.

The disproportional nature of the Senate is not just a problem of disadunder representing certain groups, but it also disadvantages the amount of funding that large states receive comparative to their population. For example, when funds from the Patriot Act were being divided up, small-state senators were able to add a provision that guaranteed each state at least 0.75% of the total grant, regardless of population. This created a situation in which small states received far more of the grant than their situation or population would necessitate. North Dakota received $92 per person to prevent terrorism, whereas New York, the site of the most devastating 9/11 attacks, received only $32 per person1.

It should be said, as well, that there are advantages to a bicameral legislature that possibly represents the minority opinion, or if nothing else provides a check on the power of the legislative branch, as perfectly elucidated by George washington himself. Upon returning from France, Thomas Jefferson was skeptical of the idea of an ‘unnecessary’ second legislative chamber. Allegedly, when asked, George Washington explained it this way3:

“Why,” asked Washington, “did you just now pour that coffee into your saucer, before drinking?”

“To cool it,” answered Jefferson, “my throat is not made of brass.”

“Even so,” rejoined Washington, “we pour our legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it.”

In addition, it is not hard to see how we ourselves might be opposed to proportional representation – if we got votes in the U.N. equal to out population size, the whole world could be bullied about by China and India, and we might be just as outraged.

Despite the potential benefits of our current system, we still have to deal with the fact that the senate was set up from the beginning as a profoundly undemocratic institution that was not designed to represent our interests. It matters – In the 2014 midterms, the 54 Republicans received 20 million fewer votes than the 46 Democrats4..

Regardless of which party or which demographics are affected, we all have to deal with the consequences of this unequal representation. Changing or eliminating the Senate is not impossible – in 1911 Victor Berger introduced a bill to abolish the Senate amid growing concerns of corruption and misrepresentation5. Two years later, in 1913, with pressure from him and others, a compromise was reached – the Senators would be elected by statewide popular votes. This helped the situation, but it clearly has not cured it. Yes, the Senate has value, but in is current state and with the constantly expanding reach of executive power from presidents of both parties, it may do more harm than good.

This is only the first in my series on representation in the United States. Gerrymandering and the Electoral College soon to follow!

- 1. Johnson, Richard. “Weighing the Costs – Nuffield College, Oxford.” Nuffield’s Working Papers Series in Politics, Oxford University, 20 Sept. 2012.

- 2. Lee, Frances E. “Bicameralism and Geographic Politics: Allocating Funds in the House and Senate.” Legislative Studies Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 2, 2004, pp.185–213., doi:10.3162/036298004×201140.

-

3. “Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.” Senatorial Saucer | Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, The Encyclopedia of Thomas Jefferson, www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/senatorial-saucer.

-

4. Matthews, Dylan. “The Senate Is Undemocratic and It Matters.” Vox, Vox, 6 Jan. 2015, www.vox.com/2015/1/6/7500935/trende-senate-vote-share.

-

5. “House Member Introduces Resolution to Abolish the Senate.” House Member Introduces Resolution to Abolish the Senate,

U.S. Senate, 9 Mar. 2018,

www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/House_Member_Introduces_Resolution_To_Abolish_the_Senate.htm.