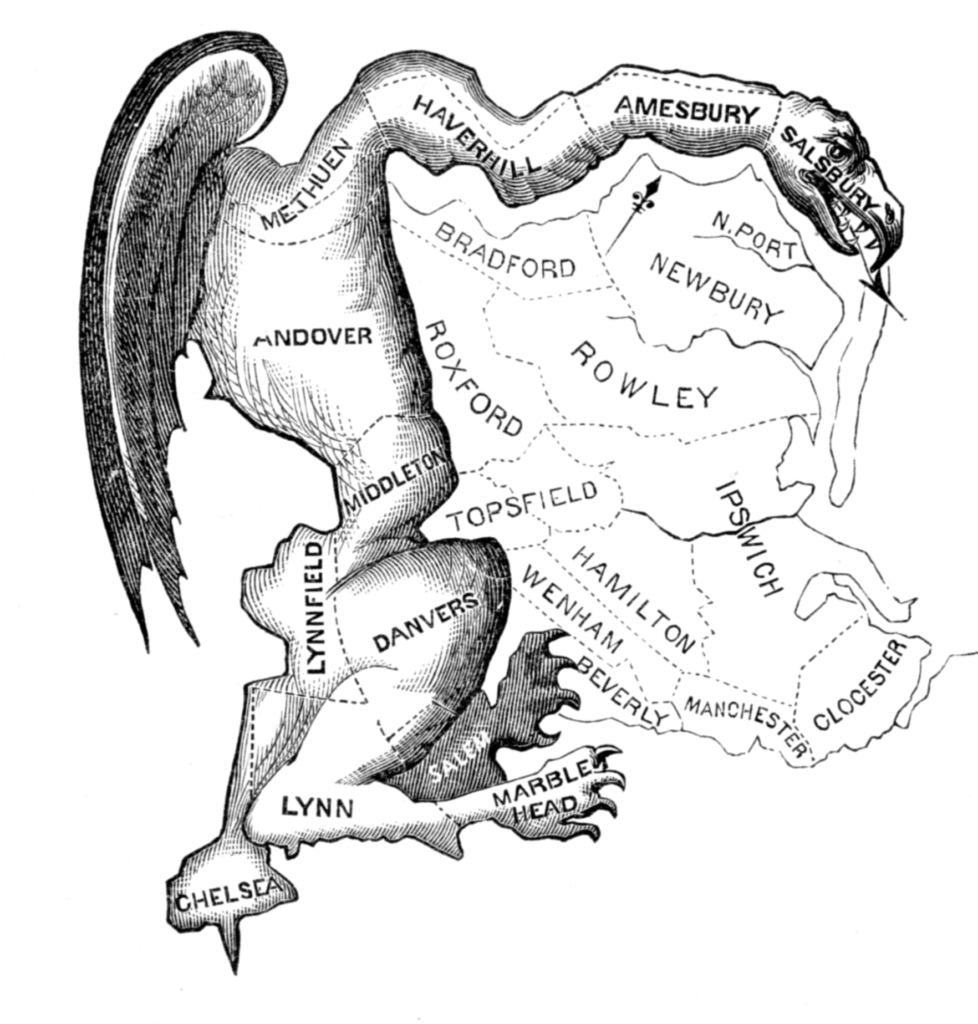

If anything can be said of the electoral college, at least it is a somewhat level playing field for the candidates. The same cannot be said of gerrymandering. The practice was initially conceived by Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts in 1812, when he passed a law allowing the redrawing of districts, and then proceeded to do so in order to give his party a massive advantage in the upcoming election. The districts he drew, just as the ones we see today, were obviously bias, with one of them famously resembling a salamander – thus giving rise to the name gerrymander.

If anything can be said of the electoral college, at least it is a somewhat level playing field for the candidates. The same cannot be said of gerrymandering. The practice was initially conceived by Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts in 1812, when he passed a law allowing the redrawing of districts, and then proceeded to do so in order to give his party a massive advantage in the upcoming election. The districts he drew, just as the ones we see today, were obviously bias, with one of them famously resembling a salamander – thus giving rise to the name gerrymander.

Gerrymandering works in one of two ways, referred to as ‘cracking’ a district or ‘packing’ it. Cracking a district works by taking an existing district that would have gone to your opponent, and splitting pieces of it off into other districts in which you will still have a majority. This spreads out your opponent’s voters from a district where they would have had a majority into a bunch of districts where they will be in the minority.

The second way in which gerrymandering is accomplished, packing a district, works by concentrating all your opponent’s voters into one district. If, for example, you had 15 voters and three districts, and 9 of them were from the opposition party, you could squeeze out a victory by ‘packing’ 5 of them into one district, and then arranging the rest of the voters 3-2 in the other districts, meaning that you win 2/3 districts even though you opponent had a 20% advantage over you.

In most cases, both methods are used in conjunction in order to create a map that favors the incumbent majority. Although gerrymandering has been around for more than two hundred years, its severity has increased dramatically over the past 10. This increase is due to the increased ability for computers to gather and compute incredible amounts of data that has developed over that time period. While gerrymandering has always been a problem, for the majority of its existence it was an imprecise science that required a lot of time and didn’t always work. Now that is changing at a rapid rate. More than ever before, we have a detailed idea of the party affiliations of voters all over the country, and computer programs written to gerrymander districts are so precise that they can draw district lines down to the street level, running through millions of possibilities to create the unfairest map possible.

Under our current system, gerrymandering is completely legal unless the opposition can prove that the system discriminates based on race or gender. While it is a relief that politicians at least can not force groups into the minority based on how you were born, it is not much better that they are able to discriminate based on your political beliefs. If you thought that, for example, gerrymandering was an unfair manipulation of the political process, and so you wouldn’t vote for anyone who you thought would partake in gerrymandering, the current representatives could split up you and everyone that agreed with you into districts in which all of you were in the minority, thus making your opinion irrelevant and allowing the politicians that supported gerrymandering to stay in power – suppressing your voice for change.

It is perhaps this example that makes the concept of gerrymandering so scary. This is public knowledge, and has been for almost 200 years, and yet no one does anything because any party that chose to draw a fair map would be at an incredible disadvantage to one that didn’t – the party in power could fix gerrymandering, but doesn’t want to because it benefits them, and the party who isn’t in power wants to fix it, but doesn’t have the means.

This cycle is vicious, and it may seem an insurmountable challenge, but is only insurmountable when we allow it to happen. When the people truly stand up to take back the power, we find that we can still make a change. Six states (Washington, California, Idaho, Alaska, Montana, and Arizona) have already switched to a redistricting model based on independent commissions, and House Democrats recently passed H. R. 1., the For The People Act, which would force state legislatures to draw districts through independent commissions.

If the idea of an independent commission doesn’t strike your fancy, you could take humans out of the matter altogether by using the same technology that has been used to make gerrymandering so dire to solve the problem — a software engineer from MIT named Brian Olsen created an algorithm that draws maximally compact districts of equal population, a process that creates sensible-looking districts rather than salamanders, and keeps politics out of the process entirely. You can read more about his algorithm in a Washington Post article here.

Despite the clearly beneficial nature and intent of such policies, they have been met with stiff opposition. In a 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court almost ruled the independent commissions drawing districts unconstitutional, and in a statement from the Senate Floor, Mitch McConnell called H. R. 1. a ‘power grab’ by the Democrats, a patently ridiculous claim considering that, according to a Bookings Institute analysis, Republicans currently hold 4.8% more seats than they deserve in the House thanks to the 2010 redistricting.

That said, it is of the utmost importance that gerrymandering does not become a partisan issue. Even the most extreme republican and democratic citizens should be able to agree that our government should be by the people and for the people, not by the government and for the government.

If we want that for our country, we have to take it back — start a movement and show our representatives that we care and will vote them out of office if they don’t make a change, because otherwise our politicians just won’t.

Gerrymandering works in one of two ways, referred to as ‘cracking’ a district, of ‘packing it. Cracking a district works by taking an existing district that would have gone to your opponent, and splitting pieces of it off into other districts in which you will still have a majority. This spreads out your opponent’s voters from a district where they would have had a majority into a bunch of districts where they will be in the minority.

The second way in which gerrymandering accomplished, packing a district, works by concentrating all your opponent’s voters into one district. If, for example, you had 15 voters and three districts, and 9 of them were from the opposition party, you could squeeze out a victory by ‘packing’ 5 of them into one district, and then arranging the rest of the voters 3-2 in the other districts, meaning that you win 2/3 districts even though you opponent had a 20% advantage over you.

In most cases, both methods are used in conjunction in order to create a map that favors the incumbent majority. Although gerrymandering has been around for more than two hundred years, its severity has increased dramatically over the past 10. This increase is due to the increased ability for computers to gather and compute incredible amounts of data that has developed over that time period. While gerrymandering has always been a problem, for the majority of its existence it was an imprecise science that required a lot of time and didn’t always work. Now that is changing at a rapid rate. More than ever before, we have a detailed idea of the party affiliations of voters all over the country, and computer programs written to gerrymander districts are so precise that they can draw district lines down to the street level, running through millions of possibilities to create the unfairest map possible.

Under our current system, gerrymandering is completely legal unless the opposition can prove that the system discriminates based on race or gender. While it is a relief that politicians at least can not force groups into the minority based on how you were born, it is not much better that they are able to discriminate based on your political beliefs. If you thought that, for example, gerrymandering was an unfair manipulation of the political process, and so you wouldn’t vote for anyone who you thought would partake in gerrymandering, the current representatives could split up you and everyone that agreed with you into districts in which all of you were in the minority, thus making your opinion irrelevant and allowing the politicians that supported gerrymandering to stay in power – suppressing your voice for change.

It is perhaps this example that makes the concept of gerrymandering so scary. This is public knowledge, and has been for almost 200 years, and yet no one does anything because any party that chose to draw a fair map would be at an incredible disadvantage to one that didn’t – the party in power could fix gerrymandering but dosen’t want to because it benefits them, and the party who isn’t in power wants to fix it but doesn’t have the means.

This cycle is vicious, and it may seem an insurmountable challenge, but is only insurmountable when we allow it to happen. When the people truly stand up to take back the power, we find that we can still make a change. Six states (Washington, California, Idaho, Alaska, Montana, and Arizona) have already switched to a redistricting model based on independent commissions, and House Democrats recently passed H. R. 1., the For The People act, which would force state legislatures to draw districts through independent commissions.

If the idea of an independent commission doesn’t strike your fancy, you could take humans out of the matter altogether by using the same technology that has been used to make gerrymandering so dire to solve the problem — a software engineer from MIT named Brian Olsen created an algorithm that draws maximally compact districts of equal population, a process that creates sensible-looking districts rather than salamanders, and keeps politics out of the process entirely. You can read more about his algorithm in a Washington Post article here.

Despite the clearly beneficial nature and intent of such policies, they have been met with stiff opposition. In a 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court almost ruled the independent commissions drawing districts unconstitutional, and in a statement from the Senate Floor, Mitch McConnell called H. R. 1. a ‘power grab’ by the Democrats, a patently ridiculous claim considering that, according to a Bookings Institution analysis, republicans currently hold 4.8% more seats than they deserve in the House thanks to the 2010 redistricting.

That said, it is of the utmost importance that gerrymandering does not become a partisan issue. Even the most extreme republican and democratic citizens should be able to agree that our government should be by the people and for the people, not by the government and for the government.

If we want that for our country, we have to take it back — start a movement and show our representatives that we care and will vote them out of office if they don’t make a change, because otherwise our politicians won’t.

I am going to vote on next Tuesday but I can’t say I am particularly optimistic about the impact my vote will have. Between the corrupt stranglehold the Republican Party has on political power and the incompetence and cowardice of the Democrats, voting feels futile. The politicians I will vote for don’t represent me and what I believe in as much as I would like them to.